Switchback

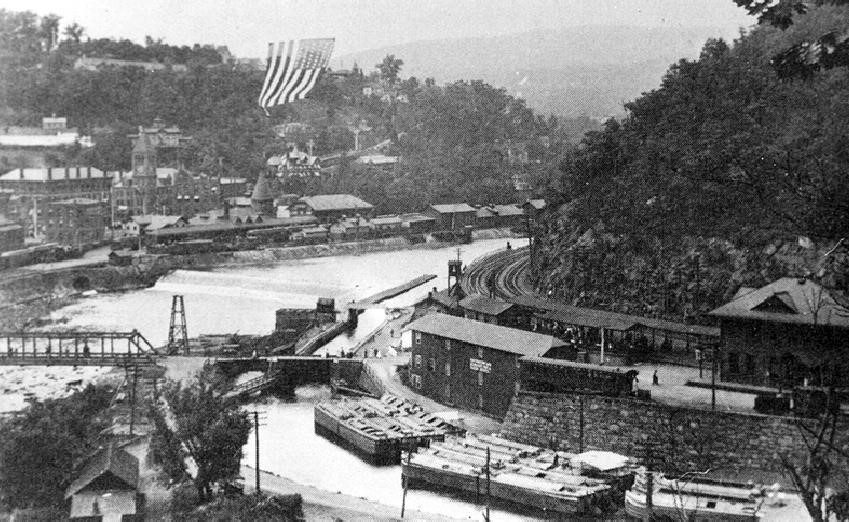

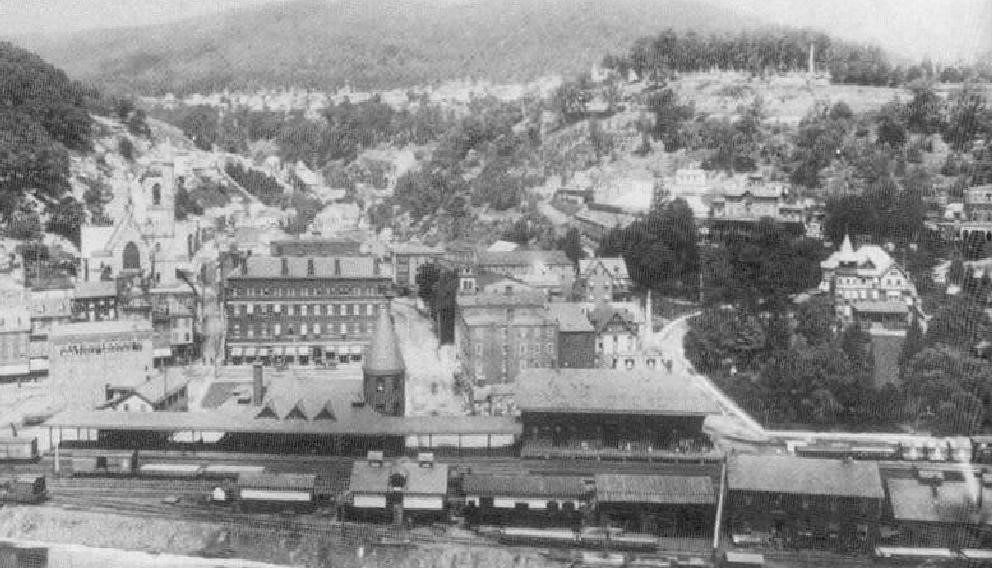

The early growth of Pennsylvania's railroads was closely intertwined with the mining of anthracite coal. In the early 1800s, Pennsylvania coal mine operators faced a daunting challenge: how to carry tons of heavy black coal from their mines to the canals and rivers below, upon which it could be transported to market. Gravity railroads were the initial solution, connecting the sources of coal to the Lehigh Canal, Delaware and Hudson Canal, and other man-made waterways that floated the vital fuel to Philadelphia, New York, and other industrial centers. In 1827, Lehigh Coal and Navigation Company constructed a gravity railroad between Summit Hill and Mauch Chunk (later renamed Jim Thorpe). It took only three months and twenty-six days to complete construction of a line measuring about nine miles in length that included nearly four miles of branch-line track that connected several mines. Freight cars rode on twenty-foot-long wooden rails that were fortified with iron straps. The cars, each weighing about one-and-one-half tons when filled, descended by the force of gravity and returned by the power of mules. In the 1840s, the addition of extra planes and another nine miles of back-track to speed the return of empty cars allowed the Lehigh Coal and Navigation Co., which owned the line, to increase both the speed and the tonnage carried, and to dispense with mule power. From this time on, stationary steam engines hauled empty cars up two inclined planes, at Mount Pisgah, directly above Mauch Chunk, and at nearby Mount Jefferson, to an elevation exceeding 2,300 feet. Excavation of the Nesquehoning Tunnel in the early 1870s ended the Switchback's service for moving coal. But the Switchback railroad soon found a second life as a popular scenic railway Visitors marveled at this early version of a roller coaster that allowed them to take in cool mountain breezes, view the Lehigh River gorge from a high overlook, and roll along with only the sound of the wheels marking the motion of the car–all for the price of seventy-five cents. The Lehigh and Susquehanna Railroad (subsequently part of the Jersey Central) and the Lehigh Valley Railroad soon brought thousands of day-trippers from major cities, filling the town's hotels and the Switchback's coffers. Set amidst towering mountains, Mauch Chunk was touted to these excursionists as the "Switzerland of America." In 1873, the Switchback railroad carried 30,478 passengers. Labor trouble in the coalfields, however, depressed Mauch Chunk's reputation as a tourism destination. From late 1875 to mid-1877, lurid tales of murder and violence, combined with the sensational arrest, trials, and executions for murder of members of the secret Irish "Mollie Maguire" organization, kept tourists away. Trials of labor activists in Mauch Chunk and Pottsville through 1876 resulted in a group of executions on June 21, 1877. On the "Day of the Rope," [as it became known], Michael Doyle, Edward Kelly, Alexander Campbell, and John "Yellow Jack" Donahue were hung by the neck until dead at the Carbon County Prison in Mauch Chunk. Tourism rebounded almost immediately after the city dismantled the gallows. But the Great Railroad Strike of 1877 in July curtailed train service on the Lehigh Valley and Jersey Central railroads, preventing tourists from returning, once more. Eventually, the Switchback recovered and, on good days, carried thousands of riders. Two of them, Nellie White of New York City and John Longley of Philadelphia, were married aboard a Switchback car on August 10, 1889. The line remained marginally profitable into the early 1900s, but World War I, the coming of automobiles, and the year-long closure in 1932 of some roads leading to town so that they could be paved, hurt business. The Great Depression sent the company into a decline that not even a community-based "Save the Switchback" campaign could halt. On Independence Day 1932, the line carried a meager 139 riders. The last cars ran in October 1933, and the line was sold for scrap in 1937.